Having recently discussed some possible SF solutions to the vexing problems posed by red dwarf stars, it makes a certain amount of sense to consider the various star systems that have served as popular settings for some classic science fiction—even if science has more or less put the kibosh on any real hope of finding a habitable planet in the bunch.

In olden days, back before we had anything like the wealth of information about exoplanets we have now1, SF authors playing it safe often decided to exclude the systems of pesky low-mass stars (M class) and short lived high-mass stars (O, B, and A) as potential abodes of life. A list of promising nearby stars might have looked a bit like this2…

| Star System | Distance from Sol (light-years) |

Class | Notes |

| Sol | 0 | G2V | |

| Alpha Centauri A & B | 4.3 | G2V & K1V | We do not speak of C |

| Epsilon Eridani | 10.5 | K2V | |

| Procyon A & B | 11.4 | F5V – IV & DA | |

| 61 Cygni A & B | 11.4 | K5V & K7V | |

| Epsilon Indi | 11.8 | K5V | |

| Tau Ceti | 11.9 | G8V |

After Tau Ceti, there’s something of a dearth of K to F class stars until one reaches 40 Eridani at about 16 light-years, about which more later. And because it is a named star with which readers might be familiar, sometimes stories were set in the unpromising Sirius system; more about it later, as well.

There are a lot of SF novels, particularly ones of a certain vintage, that feature that particular set of stars. If one is of that vintage (as I am), Alpha Centauri, Epsilon Indi, Epsilon Eridani, Procyon, and Tau Ceti are old friends, familiar faces about whom one might comment favourably when it turns out, for example, that they are orbited by a pair of brown dwarfs or feature an unusually well-stocked Oort cloud. “What splendid asteroid belts Epsilon Eridani has,” one might observe loudly, in the confident tone of a person who never has any trouble finding a seat by themselves on the bus.

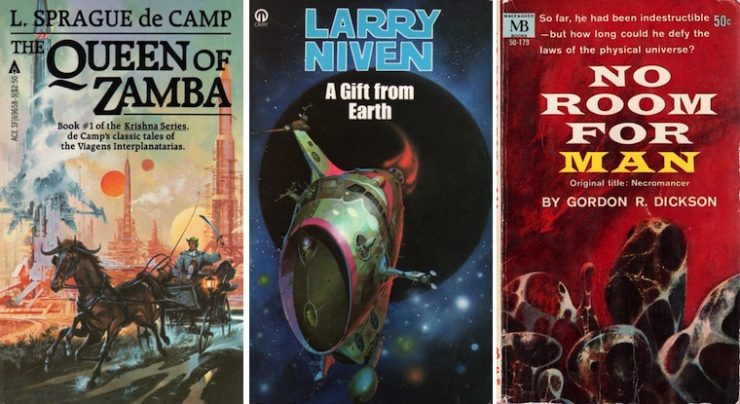

In fiction, Procyon is home to L. Sprague de Camp’s Osiris, Larry Niven’s We Made It, and Gordon R. Dickson’s Mara and Kultis, to name just a few planets. Regrettably, Procyon A should never ever have been tagged as “possesses potentially habitable worlds.” Two reasons: solar orbits and Procyon B’s DA classification.

Procyon is a binary star system. The larger star, Procyon A, is a main-sequence white star; its companion, Procyon B, is a faint white dwarf star. The two stars orbit around each other, at a distance that varies between 9 and 21 Astronomical Units (AU).

Procyon A is brighter than the Sun, and its habitable zone may lie at distance between 2 and 4 AU. That is two to four times as far from Procyon A as the Earth is from our Sun.

Procyon B is hilariously dim, but it has a very respectable mass, roughly 60% that of our Sun. If Procyon A were to have a planet, it would be strongly affected by B’s gravitational influence. Perhaps that would put a hypothetical terrestrial world into an eccentric (albeit plot-friendly) orbit…or perhaps it would send a planet careening outside the system entirely.

But of course a hypothetical planet would not be human- or plot-friendly. B is a white dwarf. It may seem like a harmless wee thing3, but its very existence suggests that the whole system has had a tumultuous history. White dwarfs start off as regular medium-mass stars, use up their accessible fusion fuel, expand into red giants, shed a surprisingly large fraction of their mass (B may be less massive than A now but the fact that B and not A is a white dwarf tells us that it used to be far more massive than it is now), and then settle down into a long senility as a slowly-cooling white dwarf.

Buy the Book

Static Ruin

None of this would have been good for a terrestrial world. Pre-red giant B would have had an even stronger, less predictable effect on our hypothetical world’s orbit. Even if the world had by some chance survived in a Goldilocks orbit, B would have scorched it.

This makes me sad. Procyon is, as I said, an old friend.

[I’ve thought of a dodge to salvage the notion of a potentially habitable world in the Procyon System. Take a cue from Phobetor and imagine a planet orbiting the white dwarf, rather than orbiting the main(ish) sequence star. We now know that there are worlds orbiting post-stellar remnants. This imaginary world would have to be very close to Procyon B if it is to be warm enough for life, which would mean a fast orbit. It would have a year about 40 hours long. It would be very, very tide-locked and you’d have to terraform it. Not promising. Still, on the plus side, the planet will be far too tightly

bound to B for A’s mass to perturb it much. Better than nothing—and much better than the clinkers that may orbit A.]

A more reasonable approach might be to abandon Procyon as a bad bet all round and look for a similar system whose history is not quite as apocalyptic.

It’s not Sirius. Everything that is true of Procyon A and B is true for Sirius A and B as well, in spades. Say goodbye to Niven’s Jinx: if Sirius B didn’t flick it into deep space like a bleb of snot, it would have cinderized and evaporated the entire planet.

It’s not Sirius. Everything that is true of Procyon A and B is true for Sirius A and B as well, in spades. Say goodbye to Niven’s Jinx: if Sirius B didn’t flick it into deep space like a bleb of snot, it would have cinderized and evaporated the entire planet.

But…40 Eridani is also comparatively nearby. It is a triple star system, with a K, an M and a DA star. Unlike Procyon, however, B (the white dwarf) and C (the red dwarf) orbit each other 400+ AU from the interesting K class star. Where the presence of nearby Procyon B spells complete annihilation for any world around Procyon A, 40 Eridani B might only have caused a nightmarish apocalypse of sorts. The red giant might have pushed any existing world around A from ice age into a Carnian Pluvial Event, but it would not have gone full Joan of Arc on the planet. The shedding of the red giant’s outer layers might have stripped some of the hypothetical world’s atmosphere…but perhaps not all of it? The planet might have been turned from a volatile rich world into a desert, but life might have survived—it’s the kind of planetary backstory Andre Norton might have used.

1: We had Peter Van de Kamp’s claims about planets orbiting Barnard’s Star, Lalande 21185, 61 Cygni, and others but those failed to pan out.

2: With slightly different values for distance and type, but I don’t have any of my outdated texts handy. Also, ha ha, none of the sources I had back then ever mentioned the ages of the various systems, which (as it turns out) matter. Earth, after all, was an uninhabitable armpit for most of its existence, its atmosphere unbreathable by us. The ink is barely dry on Epsilon Indi and Epsilon Eridani. Don’t think Cretaceous Earth: think early Hadean.

3: Unless you know what a Type 1a supernova is.

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviewsand Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is surprisingly flammable.

40 Eridani was posited as Vulcan’s home star as far back as James Blish’s original 1967 collection of Star Trek episode adaptations (which Blish did in order to differentiate it from the mythical Solar planet Vulcan that was once believed to exist inside Mercury’s orbit). This was made all but canonical in Star Trek: Enterprise‘s fourth season, which established twice that Vulcan is 16 light-years from Earth. A few tie-in works in the interim proposed Epsilon Eridani as Vulcan’s primary instead, though most went with 40 Eri.

The 1975 Star Fleet Technical Manual by Franz Joseph Schnaubelt posited Alpha Centauri, Epsilon Indi (misspelled as “Indii”), and 61 Cygni as founding systems of the Federation along with Earth and 40 Eri, though it implied that those three were all human colonies. The 1977 Star Fleet Medical Reference Manual by Eileen Palestine and Geoffrey Mandel et al. established Epsilon Indi as the Andorian homeworld (despite it being mentioned as Triacus in “And the Children Shall Lead”) and 61 Cygni as the Tellarite homeworld. The 2002 Star Trek Star Charts by Mandel et al. reassigned the Andorians to Procyon but kept Vulcan at 40 Eri and Tellar at 61 Cyg.

This is why you have a wibbly space time thing which hurtles your cast into a distant galaxy whose details we cannot make out (yet).

James, James, James! How dare you add a note “We do not speak of C” and then … not speak of C. I’m dying to know why not. Especially since the fount of all wisdom, Wikipedia, says that “whether it could support life is disputed”–“disputed” no less! You can hardly do better than that!

This post makes it clear 40 Eridani was a perfect choice for Vulcan. Desert world – check. Thin atmosphere – check.

The issue with C is that it is a dim red dwarf and a flare star to boot, so it was not (and is not) clear if an Earth-like world orbiting it would be habitable.

I have no idea why that posted twice.

To give some idea how much mass white dwarfs shed, the DA at 40 Eridani is about 100 million years old. Given the age of the system it was probably a F type star, 1.3x the mass of the sun. It’s currently half the mass of the sun so it managed to get rid of .8 solar masses of material.

I don’t know that I have read anything set in a system where a planetary nebula was forming but it would be a challenging environment.

For the record, I did try to respond to 3 but the comment got deleted, presumably because we do not speak of C.

Sorry for the confusion–the double post was unpublished, but then republished after #6 was edited. Clearly, speaking of C brings only (temporary) chaos.

This is a great topic. I want more! So please start working on some sequels.

To be honest, I’ve never bothered to check what the nearest planetary nebula is. It seems to be NGC 7293,the Helix Nebula. To give some idea how quickly some phases of stellar evolution go, the whole thing is over two light-years wide but it’s roughly the same age as Jericho. It is younger than beer.

I can still hold out hope that an Earth-like planet could be found in the habitable zone of Tau Ceti. Sure, they found four super-earths/gas dwarfs, but there is a big gap between Tau Ceti e and f where such a planet could be.

There is also the possibility, as Kim Stanley Robinson suggested in his _Aurora_, that e or f might be binary planet systems, and that a smaller satellite might be more Earth-like.

Meanwhile, if we’re speaking of 40 Eridani B and Vulcan, that star’s recent red giant/planetary nebula phase at a convenient remove can make that system a good one for a desert world like Vulcan.

I remember reading a short story where a planetary nebula was threatening an existing colony world … it was in one of the massive Cambpellian Anthologies put out by Rampant Loon Press. It wasn’t called a planetary nebula by name, though it was clear to me that was what was meant.

To speak of that which must not be spoken: Stephen Baxter set part of Proxima (published 2013) on the third planet of Proxima – it whipped around its star once every 8 days. The flaring wasn’t much of a problem for the colonists – just get into shelter when a flare happened.

Too bad about all the cancers they got. Couldn’t be helped, really.

Let’s see. We can have 40 Eri as a singleton with a nice habitable zone, but Earth has to suffer through the Eugenics Wars and a devastating WW3. Or, Procyon can be a more hospitable singleton, but then we’ve got to deal with an oppressive UN and their ARM goons. And so on.

Perhaps classic SF writers were illustrating that the vagaries of star-formation histories in our corner of the galaxy could cause an interstellar butterfly effect?

Wait, why do we not speak of C? I know we do not speak of C, but we can speak of why we do not speak of C. Speaking of C causes chaos, but speaking of why we do not speak of C would be the opposite. It would be like not not speaking of C. That would be speaking of C. Speaking of why we we do not speak of C is not speaking of C it is speaking of not speaking of C. Speaking of not speaking of C would bring order.

See?

Because back then, red dwarfs were seen as unlikely hearths for lifebearing worlds. Then they weren’t. Then they were. And now there is this:

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/full/10.1089/ast.2017.1723

Damn. I wish they’d put spoilers in the Abstract, but I think they’re suggesting it’s possible. But that’s my point from my first post: if it’s debatable/contentious, then it’s eminently fair game for SF! It’s hard to speculate about what’s already known (though we know FTL travel is impossible, and still speculate about it anyway). If somebody had proven one way or the other that a red dwarf could or couldn’t have a lifebearing world, they’d be no fun to write about.

@18/auspex: Well, technically, we know that FTL travel is theoretically possible but prohibitively impractical. We know there are several solutions of the equations of General Relativity that could allow for it, but they require an incredible amount of energy to achieve. Then again, theorists have already managed to find refinements to the equations that reduce the energy requirement from “more energy than exists in the observable universe” to “roughly the mass-energy of Jupiter,” which is a huge improvement. So perhaps some future refinement to the theory would bring it closer to the realm of achievability.

But you’re right — SF is about exploring those remote possibilities, those things that are suggested and not entirely ruled out by scientific theory. The more unlikely possibilities are the more interesting ones to explore. After all, fiction usually is about exceptional events and circumstances, not routine or expected ones.

Sigh! No planets around Red Dwarf stars? Glad MZB didn’t hear of that! We would be the poorer for the lack of a Darkover.

@20/Stan: Oh, we’ve found tons of planets around red dwarfs. It’s just a matter of debate whether they could be habitable. In fact, the conventional wisdom used to be that they almost certainly weren’t, but these days it’s more of an open question.

Hey, look! It looks like 40 Eri A may have a planet, despite the efforts of JJ Abrams…